Explosion protection design in chemical plants looks simple in theory, yet often fails in practice.

The main reason is not a lack of standards, but a lack of realistic assumptions: incomplete information, frequent plant modifications, and overly conservative area classifications that no longer reflect actual operations.

This article explains practical explosion-proof design from three fundamental perspectives:

- Release source – where flammable gas or vapor can be released

- Ventilation – how air actually moves and dilutes hazards

- Distance – how far hazardous atmospheres realistically extend

Rather than focusing on idealized theory, this article prioritizes approaches that work in real batch-type chemical plants.

Explosion-Proof Equipment in Chemical Plants: A Practical Guide for Engineers

- 1. Ignition Sources and Explosive Atmospheres

- 2. Hazardous Area Classification (Zone 0 / 1 / 2)

- 3. Release Sources: A More Practical View

- 4. Ventilation: Often Misunderstood, Always Critical

- 5. Distance-Based Thinking

- 6. Why “Everything Becomes Zone 2”

- 7. Non-Hazardous Areas Inside Hazardous Plants

- Conclusion

- About the Author – NEONEEET

1. Ignition Sources and Explosive Atmospheres

Explosion risk exists only when both an ignition source and an explosive atmosphere are present.

Typical ignition sources in chemical plants

- Hot surfaces

- Electrical sparks

- Static electricity

Explosive atmosphere

An explosive atmosphere forms only when fuel and oxygen exist within a specific concentration range (flammable limits).

Pure air does not burn. Pure fuel does not burn.

Explosion risk exists only inside this range.

Chemical plants, including petroleum, pharmaceuticals, resins, coatings, and even semiconductor manufacturing, routinely operate near this boundary.

2. Hazardous Area Classification (Zone 0 / 1 / 2)

Hazardous areas are defined assuming:

- Explosive atmospheres can form

- Electrical equipment is present

| Zone | Definition |

|---|---|

| Zone 0 | Explosive atmosphere present continuously or for long periods |

| Zone 1 | Explosive atmosphere likely during normal operation |

| Zone 2 | Explosive atmosphere unlikely and short-lived |

In theory, classification is clear.

In reality—especially in batch plants with frequent piping modifications—strict application becomes nearly impossible.

3. Release Sources: A More Practical View

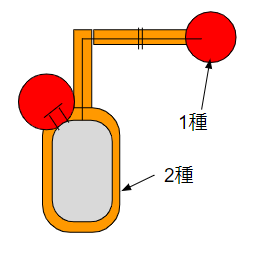

Release sources describe where flammable material can escape, and are closely related—but not identical—to hazardous areas.

| Release Grade | Typical Meaning | Rough Zone Relation |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous | Constant or high-concentration release | Zone 0 |

| Primary | Expected release during normal operation | Zone 1 |

| Secondary | Abnormal or rare release (e.g., gasket degradation) | Zone 2 |

Key reality:

- Piping, flanges, and seals exist everywhere

- Precisely defining every secondary release source is unrealistic

- Attempting perfect classification often wastes engineering effort

4. Ventilation: Often Misunderstood, Always Critical

Ventilation determines whether released gas accumulates or disperses.

Types of ventilation

- Natural ventilation (open structures)

- Forced ventilation (exhaust fans)

- Local exhaust (sampling points, vents)

- No ventilation (rare, highly restricted)

Batch chemical plants rely heavily on natural ventilation by design.

Local exhaust is increasingly applied to sampling and vent points to downgrade release severity.

A key misconception:

“Ventilation rate” matters less than where gas is released and where it flows.

5. Distance-Based Thinking

Hazardous areas expand or shrink primarily with distance from the release source.

Simplified practical logic:

| Release Source | Near | Far |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous | Zone 0 → 1 → 2 | |

| Primary | Zone 1 → 2 | |

| Secondary | Zone 2 → Non-hazardous |

In practice, defining exact distances is difficult due to:

- Variable operating conditions

- Plant geometry

- Lack of clear quantitative guidance

6. Why “Everything Becomes Zone 2”

Because:

- Secondary release sources are everywhere

- Plant modifications are frequent

- Maintaining precise records is unrealistic

Many plants adopt a pragmatic solution:

Treat the entire plant area as Zone 2,

then apply stricter measures only where truly necessary.

This avoids over-designing Zone 1 while still maintaining safety.

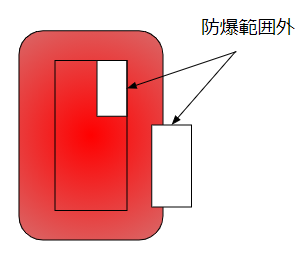

7. Non-Hazardous Areas Inside Hazardous Plants

Instrument rooms and control rooms often contain non-explosion-proof equipment.

They remain acceptable only because they are designed as pressurized rooms:

- Slight positive pressure

- Clean air intake from elevated locations

- Double outward-opening doors

- Fixed (non-opening) windows

- Multiple escape routes

Without these measures, “non-hazardous” classification becomes meaningless.

Conclusion

Explosion protection design is not about chasing perfect classifications.

It is about realistic risk control.

By focusing on:

- Release sources

- Ventilation behavior

- Distance from release points

engineers can avoid excessive investment while maintaining safety.

In batch chemical plants especially, simplification combined with targeted protection—such as treating broad areas as Zone 2 and reinforcing critical points—often provides the most practical and defensible solution.

About the Author – NEONEEET

A user‑side chemical plant engineer with 20+ years of end‑to‑end experience across design → production → maintenance → corporate planning. Sharing practical, experience‑based knowledge from real batch‑plant operations. → View full profile

Comments