Plate heat exchangers are widely used in chemical plants to efficiently transfer heat between liquids.

Compared with shell-and-tube heat exchangers, they are compact, space-saving, and offer high heat transfer efficiency. However, these advantages come with design and operational limitations that engineers must clearly understand.

This article explains the fundamentals of plate heat exchangers, how to select the right type, and key precautions in liquid–liquid heat transfer applications. The focus is on practical considerations in chemical plants, making it suitable for beginners and early-career engineers.

This article is part of the Heat Exchanger Design Series.

- 1. Principle and Characteristics of Plate Heat Exchangers

- 2. Flow Arrangement and Heat Transfer Efficiency

- 3. Plate Geometry

- 4. Sealing Methods

- 5. Materials of Construction

- 6. Expandability: A Practical Drawback

- 7. Maintenance Strategy

- 8. Liquid Sealing Risk in Batch Operation

- Conclusion

- About the Author – NEONEEET

1. Principle and Characteristics of Plate Heat Exchangers

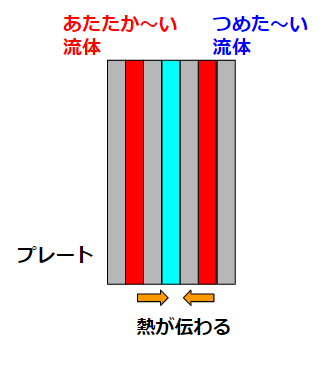

A plate heat exchanger transfers heat between two fluids separated by thin metal plates.

Heat transfer occurs through a combination of conduction through the plate and convection on both fluid sides.

To maximize efficiency:

- Plates are made as thin as possible

- Flow channels are kept narrow

This design prioritizes heat transfer performance over mechanical strength.

As a result, plate heat exchangers are typically applied only where high pressure or severe mechanical loads are not required.

Typical applications include:

- Liquid–liquid heat exchange

- Clean fluids without solids or slurry

- Non-hazardous services

These constraints mean that usable applications are more limited than they may appear.

2. Flow Arrangement and Heat Transfer Efficiency

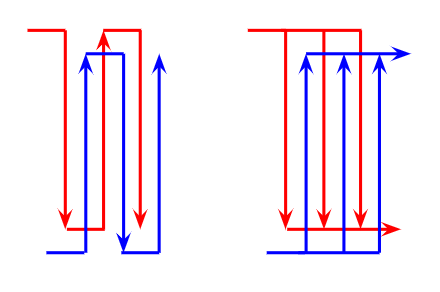

Two general flow arrangements are common:

- Alternating (cross) flow

- Parallel multi-channel flow (more common in practice)

Parallel flow offers:

- Lower pressure drop due to reduced velocity per channel

- Some natural convection benefit when hot fluid enters from the top and exits from the bottom

In batch plants, flexibility is often more important than ideal flow orientation.

Fixing inlet positions for both process and utility fluids simplifies operation, even if heat transfer efficiency is slightly reduced.

Key advantages of plate heat exchangers:

- High heat transfer efficiency

- Compact footprint (secondary benefit)

3. Plate Geometry

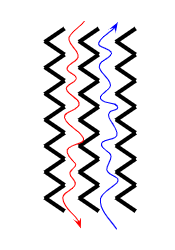

Plate surface patterns (corrugations) are used to:

- Disturb fluid flow

- Promote turbulence

- Thin the thermal boundary layer

Manufacturers invest heavily in plate pattern optimization.

From a user’s perspective, however, the exact pattern is rarely a critical selection factor unless operating at extreme conditions.

4. Sealing Methods

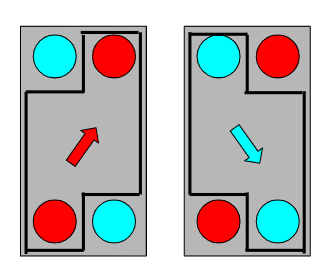

Gasketed Type

Traditional plate heat exchangers use gaskets to separate hot and cold fluid channels.

Characteristics:

- Limited gasket material options

- Not suitable for high pressure

- Easy disassembly and cleaning

In chemical plants, ease of disassembly is a major advantage due to frequent fouling and corrosion concerns. Thin plates are especially vulnerable to crevice corrosion, making regular inspection essential.

Welded Type

Welded plate heat exchangers (brazed, semi-welded, or fully welded) eliminate gasket leakage and improve strength.

However, they are rarely used in chemical plants due to limited cleanability and replacement difficulty.

5. Materials of Construction

Plates

Plates are typically made from stainless steel or higher-grade alloys.

Carbon steel (e.g., SS400) is generally unsuitable due to corrosion and crevice corrosion risks.

Gaskets

Common materials include:

- Rubber-based elastomers

- Fluoropolymer-based materials (PTFE)

PTFE gaskets are often the safest choice in chemical service, offering good chemical resistance with acceptable sealing performance.

6. Expandability: A Practical Drawback

Manufacturers often emphasize expandability (adding plates later).

In practice, this feature is frequently unnecessary and sometimes harmful.

Oversized frames reduce the space-saving advantage that defines plate heat exchangers. Expansion decisions should belong to the plant designer, not be imposed by default manufacturer philosophy.

7. Maintenance Strategy

Plate heat exchangers force a strategic choice:

- Long-term use with repeated disassembly and cleaning

- Planned replacement every 5–10 years

In harsh corrosion environments, even frequent cleaning cannot prevent plate degradation.

When cleaning costs, downtime, and manpower are considered, full replacement may be more economical.

Choosing welded types as consumable equipment can be reasonable—but only with strong coordination between design, operations, and maintenance teams.

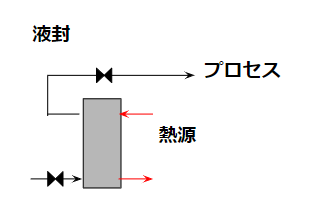

8. Liquid Sealing Risk in Batch Operation

When heating process liquids in batch plants, liquid sealing (thermal expansion of trapped liquid) is a serious risk.

If valves upstream and downstream of the exchanger are closed while liquid remains trapped, internal pressure can rise rapidly, causing leakage or rupture.

This is dangerous for any fluid—and especially critical for flammable or reactive process liquids. Proper venting and valve placement are essential design considerations.

Conclusion

Plate heat exchangers are highly efficient and compact solutions for liquid–liquid heat transfer.

However, long-term safe operation depends on careful attention to:

- Material selection

- Gasket choice

- Maintenance strategy

- Liquid sealing prevention

Understanding the strengths and limitations of gasketed and welded types allows engineers to select the most appropriate configuration for their specific chemical plant applications.

About the Author – NEONEEET

A user‑side chemical plant engineer with 20+ years of end‑to‑end experience across design → production → maintenance → corporate planning. Sharing practical, experience‑based knowledge from real batch‑plant operations. → View full profile

Comments