In vacuum systems within chemical plants, ensuring that a water seal functions correctly is a fundamental requirement for safe operation. One simple yet powerful device that supports this function is the atmospheric leg.

Although the structure appears physically simple, improper sizing or misunderstanding of operating conditions can prevent it from functioning as intended.

This article explains:

- The operating principle of an atmospheric leg

- Key design dimensions

- Practical application examples

Despite its structural simplicity, several important considerations must not be overlooked.

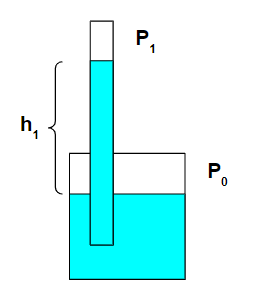

Principle of the Atmospheric Leg

The principle of an atmospheric leg is straightforward:

it maintains a water seal even under vacuum conditions, preventing air ingress into a reduced-pressure line.

A water seal is formed by dipping the end of a line into a water tank so that the line is not directly open to the atmosphere.

The governing relationship between pressure and liquid head is:P0−P1=ρgh1

Where:

- P0 = atmospheric pressure (101.3 kPaA)

- P1 = vacuum pressure (minimum 0 kPaA)

- ρ = liquid density

- g = gravitational acceleration

- h1 = liquid head height

For water:(101.3−0)×1000/1000/9.8≈10 m

Therefore, the maximum theoretical water seal height is approximately 10 meters.

If the seal liquid density is slightly higher than water, the required height becomes slightly lower.

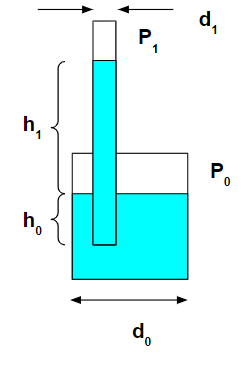

Dimensioning of the Atmospheric Leg

In principle, an atmospheric leg functions if the vertical height exceeds 10 meters. This is one reason why vacuum system heat exchangers are often installed on elevated structures.

However, proper design requires more than simply providing height.

When vacuum is applied, liquid rises inside the atmospheric leg. The dip depth must remain sufficient to prevent seal breakage even after this rise.

The required relationship can be expressed as:4πd02h0=4πd12h1

Where:

- d0 = tank diameter

- h0 = initial dip depth

- d1 = atmospheric leg pipe diameter

- h1 = lifted liquid height

If tank size is limited, careful dimensioning becomes essential. Overflow considerations must also be addressed.

Although conceptually simple, practical design requires attention to detail.

Practical Applications

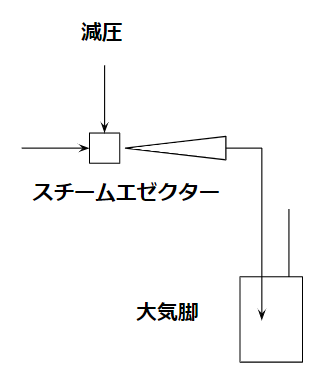

1-Stage Steam Ejector

Atmospheric legs are commonly used in vacuum systems with steam ejectors.

The ejector discharge is not fully liquid; it typically contains a gas-liquid mixture. The atmospheric leg prevents air ingress while allowing condensate discharge.

Pipe diameter selection is critical. If the atmospheric leg diameter is too small, pressure loss increases and required vacuum levels may not be achieved.

In practice, mist separation is often added before or after the ejector.

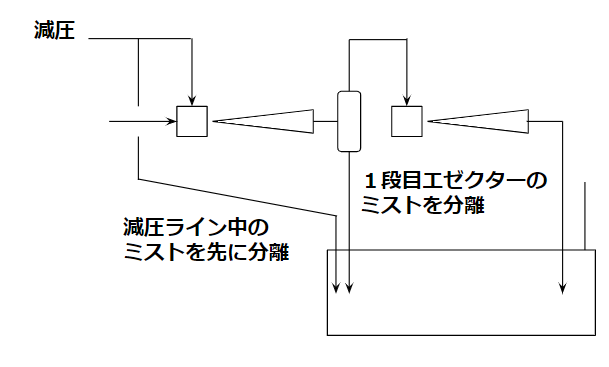

2-Stage Steam Ejector

Steam ejectors are commonly installed in multiple stages because a single stage has vacuum limitations.

Gas entering an ejector should contain minimal liquid:

- Excess liquid increases volumetric load

- Steam heat may re-evaporate liquid

- Performance deteriorates

Therefore, an atmospheric leg upstream of the first stage is often essential.

Gas should be taken from the top, liquid from the bottom — following basic separation principles.

Upstream of the second-stage ejector, a mist separator (gas-liquid separator) is typically installed. In some systems, a condenser is used to cool and condense steam before the next stage.

Atmospheric legs help prevent water carryover into downstream equipment.

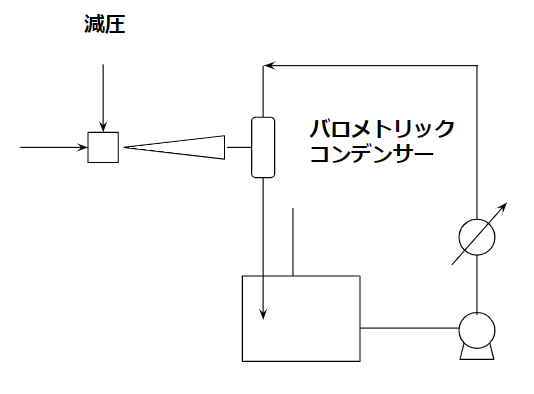

Barometric Condenser

Another common application is the barometric condenser, a direct-contact condenser.

Unlike shell-and-tube heat exchangers (indirect type), barometric condensers mix cooling water directly with process vapor. This provides higher heat transfer efficiency.

Because process and utility streams are intentionally mixed, atmospheric legs function similarly to gas-liquid separators.

The seal water from the atmospheric leg tank can often be circulated as condenser cooling water.

However, circulating liquid temperature gradually increases due to:

- Latent heat

- Sensible heat

- Dissolution heat

- Pump work

If gas absorption is required (e.g., hazardous gas absorption), higher water temperature reduces absorption efficiency. Therefore, a cooling heat exchanger should be installed in the circulation loop.

It is advisable to oversize the cooling exchanger slightly to accommodate process variations.

When water is circulated, tank level drops by the circulation loop volume. Therefore, either:

- Dip depth must account for level reduction, or

- Level control must replenish water

Summary

- Atmospheric legs are essential devices for maintaining water seals in vacuum systems.

- Proper design must consider liquid head height and pipe diameter to prevent seal breakage.

- They are widely used with single- and multi-stage steam ejectors and barometric condensers.

- Understanding the physical principle ensures safe and stable vacuum operation.

Though structurally simple, careful engineering is required for reliable performance.

About the Author – NEONEEET

A user‑side chemical plant engineer with 20+ years of end‑to‑end experience across design → production → maintenance → corporate planning. Sharing practical, experience‑based knowledge from real batch‑plant operations. → View full profile

Comments