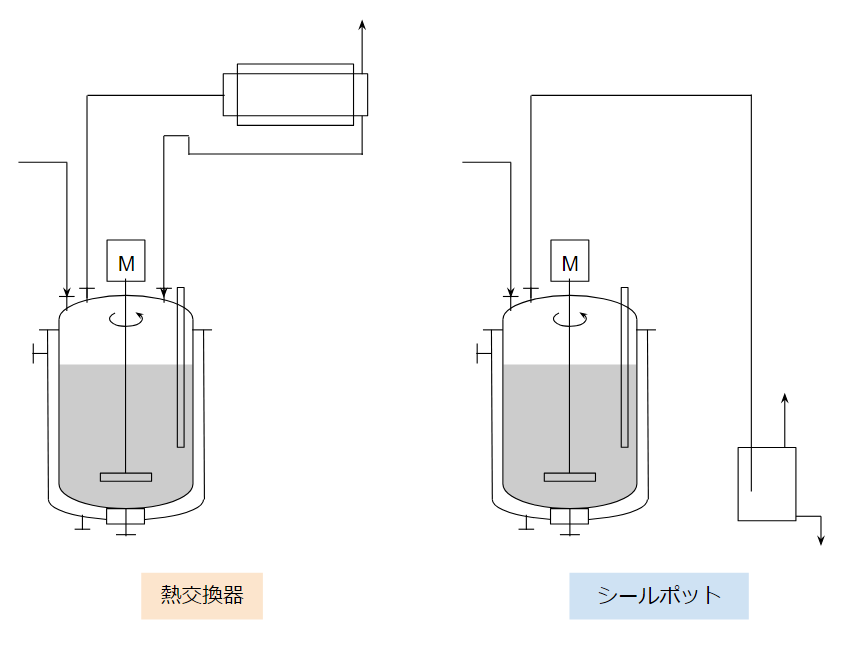

When you closely observe batch chemical plants, you will notice that some reactors are equipped with heat exchangers, while others are not.

From a standard plant design perspective, installing a heat exchanger on a reactor is generally considered the default approach, as it significantly expands operational flexibility.

However, there are also many cases where stable operation is achieved using only a seal pot.

To avoid blindly designing reactors with heat exchangers “because they are always required,” it is essential to clearly understand the functions and limitations of both heat exchangers and seal pots.

This article explains the fundamental differences between heat exchangers and seal pots and provides a practical framework for making rational design decisions in batch plants.

A Complete Guide to Shell and Tube Heat Exchangers: Key Parts and Structure Explained for Beginners

Shell-and-Tube Heat Exchangers Made Simple: A Beginner’s Design Guide for Chemical Plants

Is the Shell-and-Tube Heat Exchanger the Best Choice for Batch Plants? A Practical Selection Guide

When to Install a Heat Exchanger

There are several key reasons for installing a heat exchanger on a reactor.

Handling Organic Solvents

When organic solvents are handled inside a reactor, installing a heat exchanger is generally advantageous.

To understand this, consider a simple process where an organic solvent at ambient temperature is charged into a reactor.

During charging, gas in the vapor space of the reactor is displaced and released to the outside, accompanied by solvent vapor.

If this gas is routed through a seal pot, the seal liquid (often water) will come into contact with the organic solvent vapor.

Although this may appear safe at first, organic solvents can accumulate in the seal pot, eventually separating from the water and floating to the surface, leading to external leakage.

Even if fresh water is continuously supplied and discharged to dilute the solvent concentration, wastewater treatment becomes necessary.

Designing a seal pot system that safely handles organic solvents therefore requires considerable effort and operational control.

In many cases, installing a heat exchanger from the beginning is the more robust and safer choice.

Seal pots are often used out of necessity—for example, in outdoor tanks where there is insufficient space to install a heat exchanger.

Such cases should be regarded as exceptions rather than standard design practice.

Applying the same logic inside a plant simply because seal pots are common in outdoor tanks can be risky.

Preventing External Emissions

A primary purpose of installing a heat exchanger on a reactor is to minimize external emissions.

This applies not only to liquid charging operations but also to processes such as distillation.

By cooling and condensing vapor in a heat exchanger and returning it to the reactor, the amount of gas released to the outside can be drastically reduced.

Organic solvents often have relatively low boiling points, so even a small temperature reduction can provide a significant condensation effect.

Compared to mixing vapor with water in a seal pot—where solvents may not dissolve and can float—cooling the vapor by 5–10 °C before discharge generally results in much lower leakage.

Distillation Operations

Distillation is one of the clearest cases where a heat exchanger is essential.

Condensing vapor back into liquid form cannot be achieved without heat transfer.

In batch plants, some reactors may not require distillation, while others do.

However, since batch plants are rarely dedicated to a single operation, considering future process changes often leads to the conclusion that pairing reactors with heat exchangers provides greater long-term flexibility.

When to Use a Seal Pot

Using only a seal pot without a heat exchanger is relatively uncommon and often feels like a workaround rather than a standard solution.

Cost Reduction

The main advantage of seal pots is cost reduction.

A seal pot may cost only one-fifth to one-tenth of a heat exchanger.

Seal pots also do not need to be installed at elevated positions, which reduces construction costs.

Maintenance costs are lower as well: while heat exchangers require periodic opening, inspection, and cleaning, seal pots are typically operated with minimal maintenance and replaced when deterioration becomes apparent.

If you encounter a plant with many reactors and very few heat exchangers, it may be worth considering whether aggressive cost reduction was a primary design driver.

Reduction of Installation Space

Another motivation for using seal pots is saving installation space.

Heat exchangers must usually be installed at a higher elevation than the reactor so that condensate can return by gravity.

Using pumps instead would require additional tanks and instrumentation, increasing costs.

If a reactor is installed between the first and second floors, the heat exchanger may need to be placed near the ceiling of the second floor or even on the third floor.

In contrast, a seal pot can typically be installed on the first floor, offering a clear spatial advantage.

Conclusion

Choosing between a heat exchanger and a seal pot for a reactor does not have a single correct answer.

- If versatility, safety, and future operational changes are priorities, a heat exchanger is the better choice.

- If cost and space reduction are the highest priorities and operating conditions are strictly limited, a seal pot can be a viable option.

In batch plants, where future process changes are common, it is generally practical to select a heat exchanger as the default and consider seal pots as exceptions.

A well-designed plant is one where the designer can clearly explain why a particular configuration was chosen.

Comments