Bypass lines appear everywhere in industrial piping, yet many engineers use them simply because “they’ve always been there.”

However, a bypass line is not just an accessory—it changes operability, maintenance strategy, and even safety.

This article explains the essential logic behind bypass piping and highlights common use cases in batch-type chemical plants where careful judgment is required.

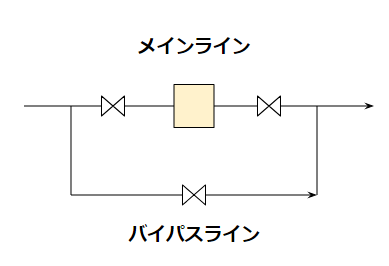

What Is a Bypass Line?

A bypass line is an alternate path that allows flow to route around equipment installed on the main line.

Normally, process fluid flows through the main line. If a device on the main line fails—such as a strainer, pump, or flowmeter—the bypass may allow temporary operation without shutting down the plant.

Bypass = a detour to maintain operation when the main line is unavailable.

1. Strainers

Strainers are classic examples where bypass lines are installed.

As debris accumulates, pressure drop increases and the strainer may clog. The bypass allows continued operation during cleaning.

However, using a bypass without any strainer has a downside: debris flows directly downstream.

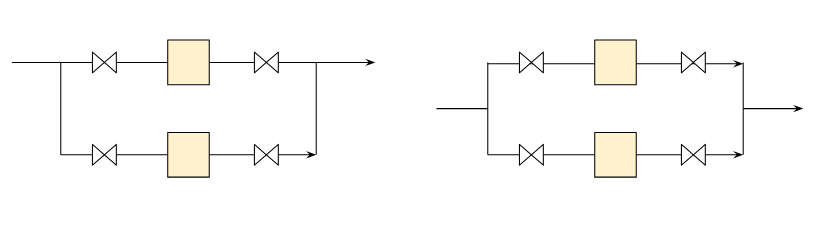

Better practice:

Install a strainer on both the main and bypass lines so that switching does not compromise debris removal.

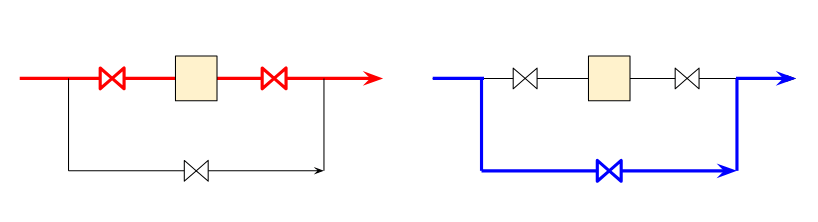

For slurry services, layout selection matters.

- A straight main line may reduce clogging.

- Symmetrical branches distribute solids more evenly.

There is no universal answer—choose based on fouling tendency and available space.

2. Pumps (Booster Pumps)

Bypass lines may appear on booster pumps placed in series.

If the booster pump fails but the process still needs minimal flow—such as emergency cooling—the bypass provides a direct flow path.

But in operations where required flow and pressure are strict (reaction feeds, precise control), a failed booster pump means the process must stop.

In those cases, the bypass serves little purpose.

3. Flowmeters

Some installations include a bypass around flowmeters, but this is only reasonable when flow accuracy is not mission-critical.

Batch plants typically stop operations when a key instrument fails, but there are exceptions—such as meters installed on cooling water sources used for controlled shutdown.

Conversely, never install a bypass around a steam flowmeter used for heating control.

Steam flow through the bypass may exceed the intended control value, creating significant safety risk.

If bypass operation is unavoidable, it must be managed manually with extreme caution.

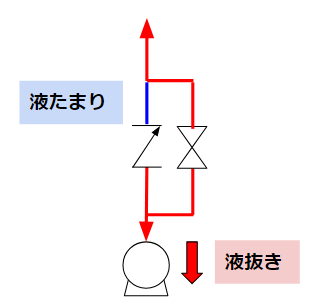

4. Check Valves

Check valves mounted vertically may trap liquid above them when the pump stops.

On restart, trapped air below the check valve can prevent priming.

A bypass allows draining the liquid above the valve and helps ensure reliable pump startup.

This is a bypass used for operability, not for failure.

5. Steam Traps

Steam traps frequently include bypass lines.

Reasons:

- Steam traps clog easily.

- Backpressure buildup can create dangerous conditions.

- Draining condensate (liquid) is essential during maintenance.

Because the steam trap is typically installed on a branch, some configurations may visually appear as if the bypass carries the trap—but the functional purpose remains the same.

Conclusion

Bypass lines are simple in concept but require thoughtful design—especially in batch-type chemical plants.

- Strainers, pumps, and flowmeters need careful judgment.

- Check valves and steam traps often require bypasses for safe and stable operation.

A bypass should not be installed just because it is standard.

Instead, evaluate whether the bypass truly improves maintainability, operability, or safety.

If you have questions about plant design, operation, or maintenance, feel free to leave a comment.

Comments